Bordering on the Sublime

I’ve always wanted to see Niagara Falls. Recently, I got my chance, accompanying my husband to Buffalo where he was to be sworn in at Federal Court. Most courts do this via Zoom or email, but the Western District insists on the real thing. We made the most of our 24 hours in Erie County.

We spent the afternoon at Niagara State Park, boarding the Maid of the Mist to observe the majesty of the falls up close. The metallic-scented spray provided a welcome respite from the 80-degree temperatures. Thanks to Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse, more than half the river’s natural flow is diverted two miles upstream to the state’s largest source of electricity. What the crowds see is more choreographed than natural chaos: in the off season, even more water is rerouted, and, in theory the plant could stop the flow altogether. Still, despite the profound manipulation, the roar and power remained awe-inspiring.

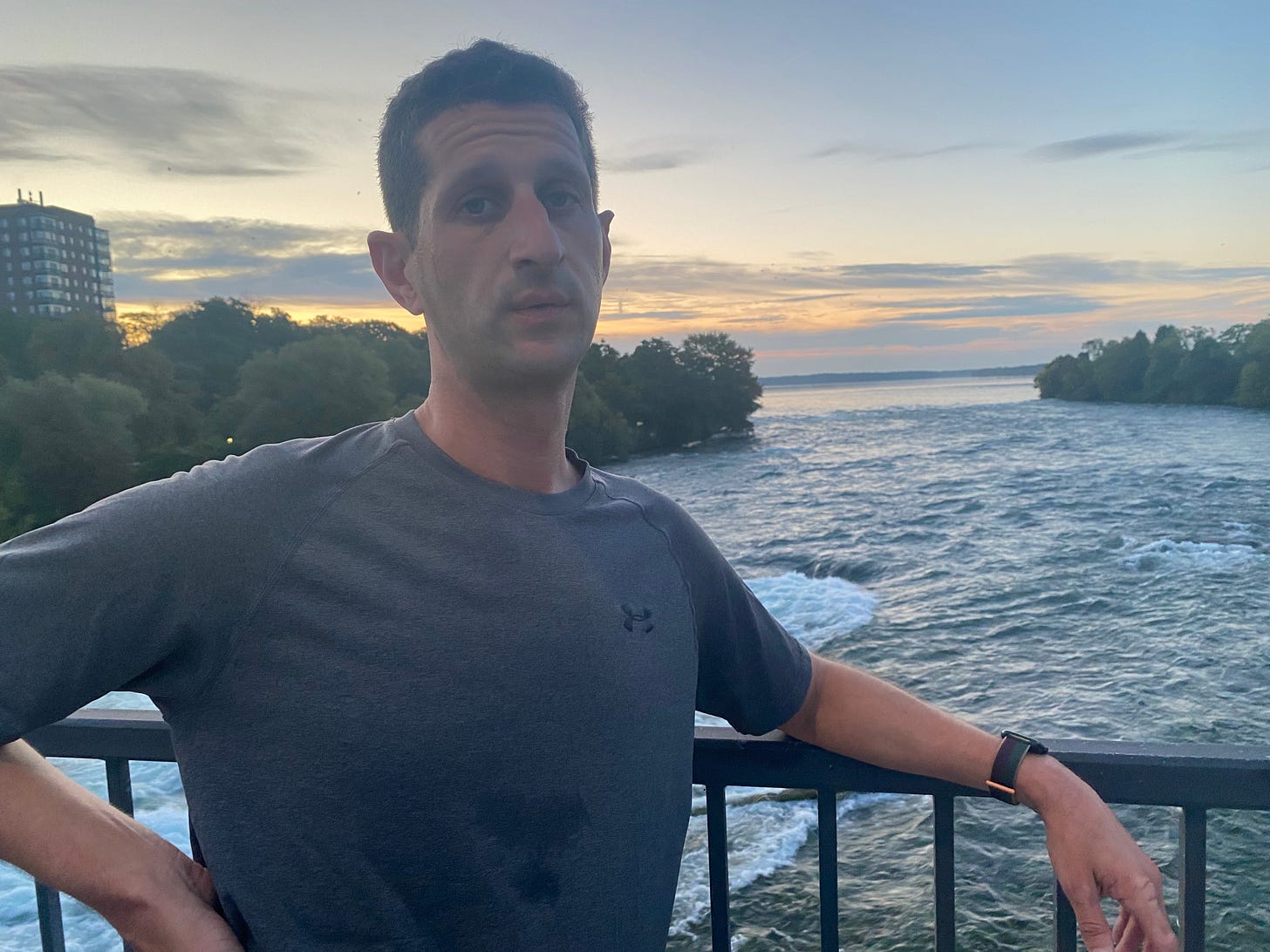

The next morning we set off early—Mike’s swearing-in was 9am. He’s not usually an early-morning runner, but I can’t function until I’ve had a caffeine hit and a run, so a 6am start was perfect for me. As we stepped out of the Doubletree and into the park, my Petzl headlamp cut through the velvet obscurity. Class 4 rapids thundered nearby, while the footbridge to Goat Island was deserted except for a state park cruiser. We expected to see other runners on this routine Wednesday morning, but we were utterly alone, the falls churning just for us. The Canadian side may be renowned for its spectacular frontal views, but nothing beats being so close to the falls you could touch them.

As we turned back, the sun rose salmon-hued above the torrent. Gulls circled nearby, and for that moment, this place balancing between wilderness and machine belonged to us alone. Even engineered and observed, the falls retain their power to move and humble. British novelist Anthony Trollope wrote in 1863 that “to realize Niagara, you must sit there til you see nothing else than that which you have come to see…At length you will be at one with the tumbling river before you…you will fall as the bright waters fall…you will rise again as the spray rises, bright, beautiful, and pure.”

We didn’t sit, but for a few quiet miles, it was just us two in that nexus of rapture and terror of an (un)natural sublime.